Bricklaid

March 21, 2025

On the twelfth kilometer of a hike in the Maule Andes, you come over a rise and it is difficult not to gasp and go, “Wow, wow, wow.” Two gigantic volcanoes, which have kept themselves hidden until this very moment, rise in close-up beyond a startlingly flat plateau. It’s a dramatic scene, to say the least!

On the left is venerable Descabezado Grande—Big Headless—majestic and relaxed in her broad slanted profile and wide crater. Jutting up on the right is her eager young granddaughter, Quizapú. Together they make an iconic and thrilling sight.

And what’s up with the freaky stone mesa in the foreground? It looks like something out of Star Wars!

It looks like an alien landing strip!

So much so, that you can forgive the many people who like to believe that’s exactly what it is, or was.

This is El Enladrillado, “The Bricklaid”, bucket-list destination for UFO enthusiasts of the world.

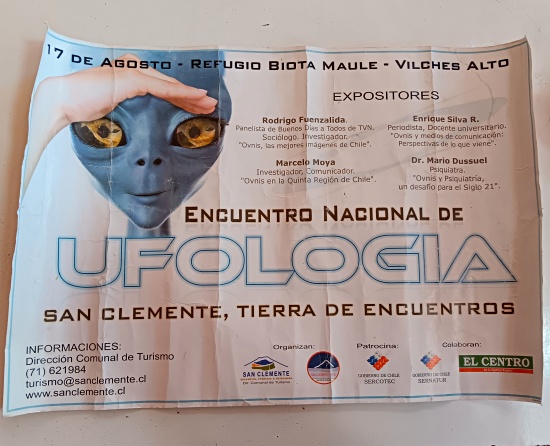

“Ufologia” is big in Chile, and the surrounding area of the San Clemente Commune is one of the world’s hotspots for OVNI (objeto volador no indentificado—unidentified flying object) encounters. Hundreds of sightings have been reported in recent decades; lots of bright lights doing impossible aerial maneuvers, humanoid figures levitating above trees, and such.

These sightings really ramped up after El Enladrillado became more publicly known in the 1970s. Of course, local people have long been aware of this curious basalt landform. Triangular in shape and about five acres in area, it sits above the treeline at an elevation of about 7,500 feet, in the pre-cordillera mountains west of the Divide. However, it wasn’t until a lot more people found out about it, and began coming here, that the UFO stuff really started to happen.

El Enladrillado certainly is an unusual formation: fractured volcanic stone resembling rectangularly-fashioned blocks fitted together like brickwork. Over 220 units in all, they appear as orderly tiles, sterile and unnatural amidst the spectacular wild landscape. It’s easy to see how someone would think this had to be man-made, perhaps alien-assisted; installed eons ago during some ancient unknown civilization to create a sacred place for extraterrestrial visitors to land. Given the beauty and energy of the surroundings, it’s a great location for our fertile imaginations.

I found myself running across the tiles, needing to get to the edge and take in the full view of an ocean of mighty mountains, and the Rio Claro, which flowed below through a seemingly limitless wilderness. I sat down on the mesa edge and snapped a bunch of pictures.

Then I began to feel incredibly tired, so I laid down on a sun-warmed brick and slept for an hour. As such, I can attest that this place has a distinct energy. For me, it’s a calm energy. Of course, this could have had something to do with my long workdays at the winery-qua-cider house eighty miles away, from which I was getting a much-welcomed respite. Perhaps it also had to do with me finally meeting my Andes. Finally! I had greeted Descabezado Grande and Quizapú up close, after admiring them for years from a distance, from my perch on Caliboro Hill above the winery.

I could rest, now. When I came to, I rolled over on the brick and studied it up close. This piece of pyroclastic flow, which settled and cooled here to give me this privileged view, had been deposited probably some time in the last million or two years, putting it in the late Pleistocene. Deposited and cooled, it had been fractured and worn away by actions of ice over eons.

This brick was totally amazing. I felt no urge to attribute it to something unnatural, man-made, invisible wizard-hewn, or otherworldly. Rather it was the natural, magical Earth just being itself. There is nothing more amazing than reality, nothing more fantastic than the story—the real one—that presents itself in front of us every day.

I gazed across the plunging Rio Claro valley to Volcán Quizapú.

Younger, much younger than the strange stone plateau on which I was brick-laying, is Quizapú. To me she is the star of this story. Only in the most recent epoch, the Holocene, did her gorgeous cone arise—sometime only in the last 11,000 years or so! A tiny blip in time!

Strictly speaking, she’s a secondary chimney of Descabezado, and together they are responsible for some of the biggest eruptions registered in South America since the Spanish arrived. Her current crater, hidden from view on the north flank, burst out on November 26, 1846.

This was when some arrieros, or backcountry herdsmen, were camping about the same distance from her as where I was brick-laying. Late that afternoon, they heard a huge explosion and saw a cloud of ash. Night fell and was full of continuous roar, blue flames, thunder, lightning, and choking sulfurous gas that sent them scurrying. Of course, they had to come back later and look for their animals. When they did, they encountered a hot lava field. And a new crater-mound.

Eighty-six years and fourteen eruptions later (including a really big one in 1932 that was likely the strongest eruption on the continent that century), we have the beautiful brand-new mountain we see today, soaring over the strange, bricklaid plateau that predates it by an unfathomably long expanse of time.

Which is, itself, also only a blip in time.

Cider House

March 10, 2025

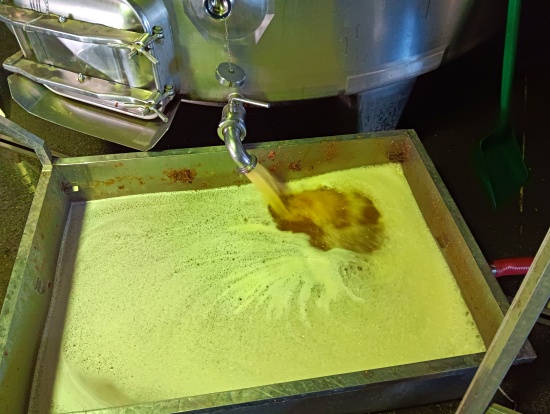

“Pete! Come watch the first test!” my foreman called to me, here at the 150-year-old winery in Chile where I am working my third season.

I paused my barrel washing operation out on the back dock and came around the corner just in time to see Javier, the General Manager, toss a shovelful of apples into the inlet hopper of our new crushing machine. The apples fell in, and then immediately blasted back out in a thousand pieces to rain—actually, snow—down on us.

Hmmm, we all thought, our hands on our chins.

Wait a minute, you might say. Apples in a winery? What’s going on?

“We’re making cider this year,” Javier texted me, late last year when I wrote to confirm my dates. “For a Brazilian client. Muuuuchos kilogramos.”

This sounded great to me. A new process to learn, in the same gorgeous late-summer-turning-to-Chilean autumn, at the same remote, historic bodega at the base of Caliboro Hill. With the same good-natured, tightly knit team. The same sunsets, the same stars, the same shimmering Andes—except this time, the graceful adobe structure would be filled not with the sweet smell of fermenting grapes, but rather with crisp apples turning to hard cider.

Fortunately, the “it’s snowing apples” incident was mostly due to the crusher’s motor being wired backwards. Once that was fixed, however, we still had quite a bit of fine-tuning to go through in order to move our first (of five) large-scale batches of locally-grown organic apples through the facility.

It’s now two weeks later and it’s been apples, apples everywhere. Many lessons have been learned. Some lessons have been obvious, such as never, ever spill a bin of apples onto the ground from the forklift because that means thousands of apples will need to be picked up, one by one, by hand.

Other lessons were not so obvious, such as: how high to fill a tank with fresh apple slurry? We filled our first 17,000-liter tank on a Thursday, and on Saturday morning I was greeted by hundreds of pounds of apple goo that had swollen up overnight through the tank’s top opening and run down the sides to pile up on the floor.

For your information, two-day old crushed, aerobically fermented apples have the exact same hue and texture (but thankfully not the aroma) of blown chunks—of the human variety.

How does it taste? Delicious, of course! At least for the first few days. My favorite day of the fermentation is day four; by then the juice is still very sweet but has a little bit of fizz and kick to it. After day nine or ten it gets quite bitter and pulpy, with of course even more of a kick, one that I have no business experiencing while climbing ladders and operating heavy equipment.

It has taken a lot of effort, with some long days in which we’ve continued working while the late summer sun set beyond the poplars. As of now, the first three tanker trucks of fermented apple sludge are making their way 1,700 miles, across the Andes and Argentina, to Caxias do Sul in southern Brazil. There it will be further processed into vinegar, bottled, and shipped around the world. In the next several years, should you go to Whole Foods and purchase a bottle of high-end, organic apple cider vinegar, it’s quite possible that I will have had something to do with it!

Literally. A few afternoons ago, I had to go inside some of the tanks in order to shovel out stubborn apple sludge that had settled on the bottoms and failed to fall out and get pumped through our fat “anaconda” hose out to the waiting tanker truck.

As I schlepped monochromatic brown goop with a plastic shovel (goop which was by now the color and consistency of another bodily substance which we definitely do not need to talk about), feeling a little high on the fermentation fumes still present inside the tank, I thought: I miss the grapes. Not because the grapes are any easier to process—in fact, they are a lot more difficult, and require entering each and every tank to shovel out the skins for pressing. The grapes get everywhere, and they’re enormously messy and tedious, but they are also gorgeously colorful: radiant blood reds, heart-swooning violets. And of course they smell amazing.

“I miss the grapes,” I said to Cecey, our laboratorian, later, as she crouched in front of a graduated cylinder filled with tan cider to measure its density.

“Me too,” she said. “So vibrant, so beautiful!”

We both smiled.

“Come,” she said, standing up. “Help me replace the telas.”

She led me to our open-air, low bay area, where seven square vats of crushed Grenache, and four of Pais—Chile’s iconic, old-school grape—were slowly turning into rich red wine. Yes! This dear old bodega is mostly about apples this season, but still making some wine, like it has done for more than a hundred and fifty years.

Mmmm, I thought, inhaling the aromas, as Cecey and I lifted the white silky telas (cloths) and draped them over the vats to cover them, thus allowing the vats to breathe while keeping the flies off.

I hadn’t been this enthusiastic a week previously when, early in the morning in my room, while donning my steel-toed shoes in preparation for another day of cider processing, I received a text from Javier:

I need you to join the harvest today.

“Ugh,” I immediately thought, as I removed my shoes and slid into lighter-weight hiking boots, and reached for my industrial-grade grape cutting scissors that sat on a window sill.

It’s always like this for me in the morning prior to going to harvest. The idea is a bit much to deal with: of a full day spent trudging through tall grass, reaching through bushy old vines to surgically remove the bunches of manna, tossing them into a white plastic hand-crate, hefting the crate and trudging all the way back to the truck to leave it and get another, all under an eventually very hot sun.

Then there’s the aspect of the old-school field guys I’d be working with, whom have been doing this their whole lives, whom can get a bit impatient and irascible with someone like me who can’t pick as fast as they do, or always know which row I should be working on, or understand their rapid-fire, thickly-accented yelling of where I need to go next.

However, I always start to feel better as soon as I get out into the sparkling morning and hop up onto the flatbed trailer with other teammates, off to go join the men out in the fields. So nice, to get a reprieve from the bodega! And to be outdoors, in the fresh air amid the grape fields, beneath the Mediterranean-esque rise of Caliboro Hill, with lofty Andes in the distance.

The first few crates of grapes for me are always a struggle. Then, as the morning progresses and the sun grows warmer, I get into a rhythm. It gets easier to find the grape bunches and locate the best places to snip them. My crates fill up quicker, one after another, and the hours go by. When it’s time to go, I almost don’t want to. I want to keep harvesting! Especially if there are still grapes out there that we need to go and get.

But of course, I am always grateful when we are done and climbing back onto the truck, exhausted, dirty, sweaty, ready be conveyed back to the bodega for much-needed food, hydration, and rest.

This day was no exception. In fact, it was something more.

“It is an honor, really” I said to my friend Felipe, a young Chilean sommelier, who was standing next to me on the trailer, who like me is here for the peak months to live and to learn.

We gazed at the rows of irregular, bushy, twisted, knobby vines growing out of the tall brown grass: vines that are at least a hundred years old. Maybe even two hundred years old.

“It is an honor and a privilege,” I continued, “To get to harvest the old País. To be a part of something so central to Chile’s—what is the word for it? In English, we would say, ‘heritage’.”

“Herencia,” Felipe said, nodding.

“It’s true,” he added, a moment later. “This is Chile’s heritage, and it is vanishing. So many of us are not even aware of it. Millions of people live in Santiago, who have never been outside of Santiago, and who have only a vague, romantic notion of the countryside and this way of life. They have no personal experience with it.”

By now it was mid-afternoon and the sun was hot and high. Near to us, Don Miguel crouched in the thick shade of an old País vine, wearing his trademark wide-brimmed hat. He was chatting with Don Leo, our tractor driver, who was finishing his cigarette before we’d go. Miguel would not be joining us on the flatbed, however. His horse was tied to a nearby tree.

“These men, too, are our heritage,” Felipe said to me, more quietly, as Don Miguel broke into a laugh and said something to Don Leo that I didn’t understand.

“They, and their huaso way of life. Like the País, these guys are vanishing. They can be prickly, hypermasculine, difficult to be around sometimes. But it is an honor and a privilege, to get to work alongside them.”

The Seahorse

February 9, 2025

Imagine it’s the 1970s in Chile and you are imprisoned and tortured on an island. Blindfolded and naked, you are hung upside-down and receive electric shocks, beatings, and humiliation daily. The horror, pain, and fear barely ebb as you are thrown back into a pitch-dark cell, where you are deprived of food and water and await more such treatments the following day. But the terror rises to new heights when they come to pull you from the dark, throw a blanket over your head, and march you back to the lavatories of, say, a former school for naval sailors, where you will be tortured again.

The only thing you can see, the only daylight you have seen for weeks, for months, is the faintly-illuminated floor passing beneath your feet. Then it appears: a bronze grate in the bathroom floor drain, fashioned in the shape of a seahorse.

How would it feel, to glimpse that seahorse?

Seahorses and Chile go way back of course, as does pretty much anything to do with the sea. When a country is 2,700 miles long and only about 112 miles wide, a lot has to do with the sea. Sea creatures are part of everyday life, and naturally have long found their way into folklore and mythology.

Perhaps nowhere is this more prevalent then in the Chiloé archipelago, in the moody, drenched, temperate rain-forested mid-south. Here a distinct mythology developed separate from the mainland, a potent mix of two indigenous religions injected with Spanish legends and superstitions compliments of conquistadors who arrived in the 1560s. For hundreds of years after that, Chiloé carried on in near isolation, as the mainland Mapuche expelled the Spanish to regions farther north and the folklore of the archipelago seasoned and ripened on its own.

A good example is El Calueche, a phantom ship that is believed to be a living being. In service to the king of the seas (whose name is Millalobo), it sails for eternity, clearing the sea of dead drowned bodies which are delivered to it by three members of the royal family. On board, the corpses are brought back to life to man the ship, in zombie form, under the watch and care of supernatural beings.

The ship is said to be shining white, with three masts and five sails. Lights blaze in its windows and the sounds of music and revelry can be heard, but it disappears when anyone tries to go near it (it is believed that it can travel underwater). In addition to the crew and managers, brujos—which are warlocks or sorcerers—often come on board to participate in the festivities.

Here’s where the seahorses come in. For reasons unknown to mortals, the brujos are forbidden to join the ship by donning their flying vests or changing into birds, which normally they can readily do. Instead they must go to the shore a few minutes before midnight carrying a sargassum seaweed bridle, and make four special whistles to summon one of their personal seahorses. When their steed arrives, a brujo will carefully and gently establish contact before restraining it with the seaweed rope, and then climb on its back to be conveyed to the ship.

These seahorses are invisible to normal eyes, but anyone can detect their presence by observing the movements in the water among shoreline rocks. To the brujos, they are dark yellowish-green in color, resulting from their diet of seaweed. They live short lives of only four years, after which they turn to gelatin and dissolve. This means that brujos must regularly obtain new seahorses, which they presumably do while El Calueche is traveling underwater. On encountering a subterranean flock while sailing with the ship, a brujo can brand his personal mark on a new steed of his choice, and thus place it devotionally into his service.

Sure, this is an uncommon myth specific to Chiloé. But the seahorse itself, as a symbol, as a motif, is and was hardly uncommon throughout Chile.

In fact, if you were one of 3,200 people who disappeared during the Pinochet dictatorship, or one of tens of thousands more who were detained and tortured, but survived, in one of the approximately one thousand torture centers that were set up, up and down the country, it is quite possible that the seahorse in the bronze drain plate was something you encountered as part of your experience.

How would it have felt? How would you have reacted, to see this image appear before you as part of your brief, sole flash of daylight?

Would the seahorse look like a monster, coming to usher in imminent horrors? Would it bring a new rush of queasiness, fear, and panic?

Or would it bring something else?

Curiously, the drain plate seahorse took on an entirely different, more positive significance for many of the sufferers. Instead of being seen as guarding the gates of hell, it rather became a symbol of resilience. Many detainees later reported that glimpsing that golden flash of the seahorse in the drain grate was the only nice thing they experienced, and it made them forget, just for a tiny little bit, what they were about to go through. It gave them a small ray of hope.

Sometimes light could be seen through the portal beyond the seahorse: light leading to the outside, reminding them that there was an outside world, another place where the evils and the rage could fade, where a person could be cleansed of suffering. The long tunnel that began at the seahorse, at some point, undoubtedly reached the freedom that everyone longed for.

In the flash of the moment, in your mind, you could climb on the seahorse’s back, and be conveyed to a different place: To a new life, or if not that, to an afterlife free from pain.

Lotería for a New Year

January 10, 2025

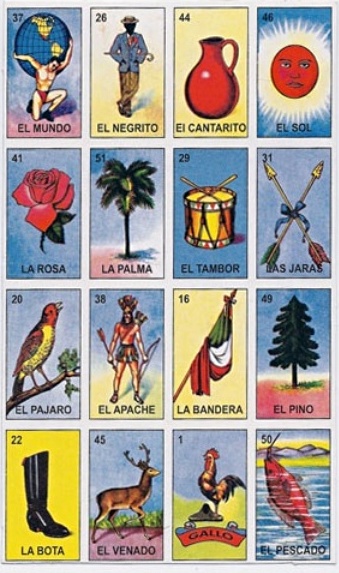

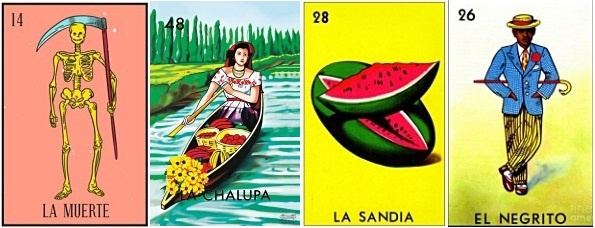

The Mexican Lottery, as you may know (I didn’t, until now) is a cherished bingo-like game that goes back hundreds of years. In it, each player chooses a uniquely-arranged 4 x 4 board of images. Meanwhile, the Singer shuffles a deck of 54 cards and prepares to sing or call out the images.

How do you win? Get four in a row, of course! Or in a column, or on a diagonal, or in the four corners, or four in a square. Mark your spots with pinto beans or corn kernels and shout “¡Lotería!” before anyone else does, and you win! Or for a longer-form game, be the first to fill out an entire board.

It’s a game everyone can play, and it is full of feeling, nostalgia, and retro charm.

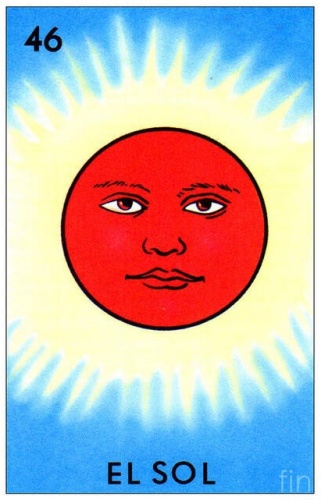

The singing is very important, and here’s where the game goes somewhere that Bingo does not. Lotería is all about being creative with words and verses, thus amping up the enthusiasm of the players. Each singer has poetic license to inject their personality and intellect, and sing out an improvised verse in clue-form to add wit and complexity to the game. For example, instead of simply calling “The Sun,” you might sing, “The coat of the poor…the Sun!”

Depending on context and setting, the singing can get very creative and topical and, of course, risqué. In this respect Mexican Lotería is much more than Bingo (although I don’t want to discount what some callers of the latter game, especially the campy-naughty variety, have been able to do with material such as “B-8”and “O-69”. I even wrote a novel about it, called The Rooster’s Hindquarters.)

Lotería arrived in Mexico in the late 1700s from Italy by way of Spain, and within the next century it became distinctly Mexican. This status was solidified in 1887 when a definitive version was published, which is known as the Don Clemente Gallo version. Originally issuing 10 boards and 80 cards per set, the company exists to this day and still owns the trademarks to the iconic images.

Don Clemente Jaques was a French businessman who bought a factory in Mexico to make all kinds of things such as corks, bottles, ammunition, and especially, packaged food for the nation’s soldiers. Naturally there was a printing division that made labels, advertisements, party supplies, and the like, and in this division the game was printed. Being on hand, it got inserted into care packages for soldiers, something for them to enjoy to pass the time.

When the soldiers brought the game home, it really took off. Over subsequent decades, Lotería became a mainstay of traveling fairs that were set up on weekends in widely-dispersed towns. Many people came to these fairs expressly to play Lotería.

Lotería might be viewed on three levels, depending on how deep you want to go with it.

On one level, there’s all the language and word-play. For example, one might sing, “He who waits (espera), despairs!” Imbedded in this is verse is es pera, or “It’s Pear.” Or “It jumps but doesn’t see anything (no ve nada),” a play on Venado, which is Deer. Or the verse might be more riddle-like, such as, “The mute one who nonetheless died by mouth.” This would be Pescado—the caught, Dead Fish (not to be confused with pesce, which is a live fish, although there is no card for that).

On another level, each Lotería card is a window not just into Mexican culture, but into the history of popular age-old feelings in the country. The pictures tell of ideas that existed in the middle of the 1800s, and are iconic representations of objects and characters from folklore, history, and everyday life. Simple in appearance, they are far from simplistic; there is so much that meets the eye. Each comes from a deep well of story and emotion.

For example, for The Bottle we might naturally sing, “The tool of the drunk!” But in many early versions of the game, the bottle in question had a tomato on the label. Is there anything more Mexican than salsa? That tomato changes the story, and the song.

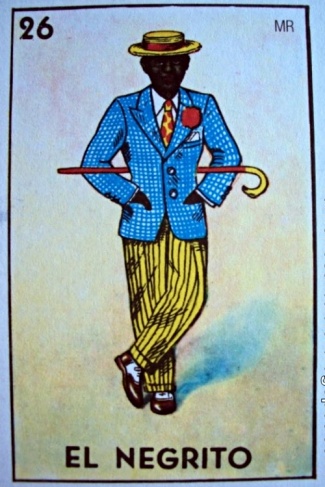

Someone could get pretty offended by El Negrito, the Little Black Guy, if they wanted to. But like all the cards, there is story and context. First off, the use of the diminutive form of El Negro is a term of endearment, and not an indicator of size. And although his clothing is very 1930s, El Negrito holds a very deep meaning that goes back an additional 100 years, one that is part and parcel to Mexican identity itself.

José Vasconcelos was a descendant of African slaves who was born circa 1820 in the state of Veracruz, or maybe it was Puebla. Though Black, he was Mexican, and a talented one at that. He had an extraordinary ability to rhyme, and he became quite known and admired for his wit and humor—a gifted wordsmith in other words, someone who embodied the spirit of Lotería.

One story has José going into a bar where the Spaniard barkeep extended his hand to shake. When they clasped hands, the Spaniard pulled both their hands to his butt and farted. Unflinching, José held his head high amid the laughter, and when he met the Spaniard a second time in a different bar, it was José who pulled hands to butt and farted—and delivered a funny impromptu rhyme about it.

Through José, El Negrito was born. By the mid-1800s every puppet show required an El Negrito character. Then came the “Pastry War”, i.e. the short-lived French invasion of the 1860s, and El Negrito became even more important: as a cheerful and talkative character who always came out proud and in a fine mood. In this way El Negrito came to represent not an outcast, but the oppressed Mexican people themselves who, despite adversity, come out proud and in a good mood—traits that have always characterized the Mexican people. In this way, El Negrito is an icon of what it means to be Mexican.

A third level of Lotería might have to do with the undeniable energy in the cards, the deep experiences of life that they resonate. Gazing at them you might think, “I’ve seen this before.” Indeed, they are archetypes. Many have analogs in the Tarot and Lenormand systems.

True, Lotería as a bingo-game is one of chance, of fate. But what if you could choose your lottery? Choose your fate? I know it sounds like a contradiction, but…

What if, as a different game, we let the cards be a fun tool—a vehicle—to choose our fate? We all do it anyway, after all, whether we want to acknowledge it or not. Every day we all choose where to direct our energy and intentions.

Here’s the game: Pick a card, any card. Actually, pick four cards, to be your Lotería hand for the coming year. Pick some good ones, ones that mean something to you!

Which ones would you pick?

Here are mine for 2025, to keep in mind and carry with me, so to speak, in my back pocket:

Death

This is a positive card! It’s about transformation and evolution, change of cycle, renewal. It’s about casting off the old and receiving the new. An area of life, an era, has ended. Roles are shifting.

The Chalupa

This is about feeling calm and adaptable while navigating uncertainty and transition. It’s also about self-determination, and being emotionally balanced and feeling powerful. It’s about choosing how to deal with things.

The Watermelon

This embodies love, life, and abundance! I’m thinking of Frida Kahlo’s near end-of-life masterpiece, “Viva la Vida”. Also, The Watermelon represents that, no matter how hard something seems, there is always a parallel, tender, sensitive side. Everything has a tender and sensitive side.

El Negrito

He’s my reminder to have fun, experience joy, take life with humor. Don’t be so serious all the time. Look for the good side, the bright side, the happy funny side of everything. Keep a good mood. Come out proud and always in a good mood.

Happy New Year!